The 155-pound newborn

The last time I was nervous about taking my son home from the hospital, he weighed around eight pounds. He was nearly hairless and his conversational abilities were limited. When agitated, I soothed him with milk and swaying and sometimes milk while swaying. When my son was a newborn, I watched him breathe as if my gaze was imbued with protective powers. We were tender with him as we did small things, like pulling a little shirt over his big head. He was our burrito, our bunny, our little man. He grew quickly. Those first nerves melted away to be replaced with newly exposed conundrums. Will he ever make peace with the potty? Where should he go to preschool? Why does he have a difficult time making friends?

We had a family meeting at the hospital. Present: Our son, my husband, a psychiatrist, a social worker, me. The main topic was planning his discharge, demonstrating we had after-care appointments set up with a therapist and a doctor. Our son shared his safety plan and things he learned about coping. The doctor warned he’d have bad days, even days when he thought about dying, and that was to be expected. The key to meeting these challenges head-on is how he deals with those feelings.

Suddenly, I pictured my face hovering above his to make sure he was still breathing. I was going to stalk him with questions regarding his current state of mind, feeling ashamed I knew myself so well. Would he have a moment of peace once home, or was I going to stare at him and agonize over a frown until I gave him a reason to frown?

When he was a newborn, I protected him from cold, hunger, falls, viruses, loud noises, and diaper rashes. There are many enemies of the newborn baby.

Now, his biggest enemy is housed inside that sweet, still-big head. I cannot pull him in from that cold.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

He is home.

We asked if he’d like a special dinner to celebrate. Without hesitation, he listed off his favorite foods and we made it happen. It was delicious. We laughed a lot as we ate together around the table. From the outside, it probably looked like the dinner of a happy family. I couldn’t simply relax and enjoy the moment. The entire time, I wondered if it met his expectations. Was it making him happy? I want to make him happy. This broth is perfect! I gushed, hoping internally he’d agree it was so good, it was worth living for. Did he want some chopped cilantro, what if all it needed to make it stellar was chopped cilantro?

I’m putting enormous pressure on myself to inspire his happiness while knowing it’s foolish to count on things like a well-seasoned broth or a well-timed question. Unless he loves himself, likes himself, and feels hope, that brand of happiness is shallow and easily crushed.

I don’t want him to buckle under the million-watt spotlight of our focused attention, the weight of our stares, the bright wide smiles. We’ve never acted like this before, or have we?

He is not a newborn, but surely he is new-born.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

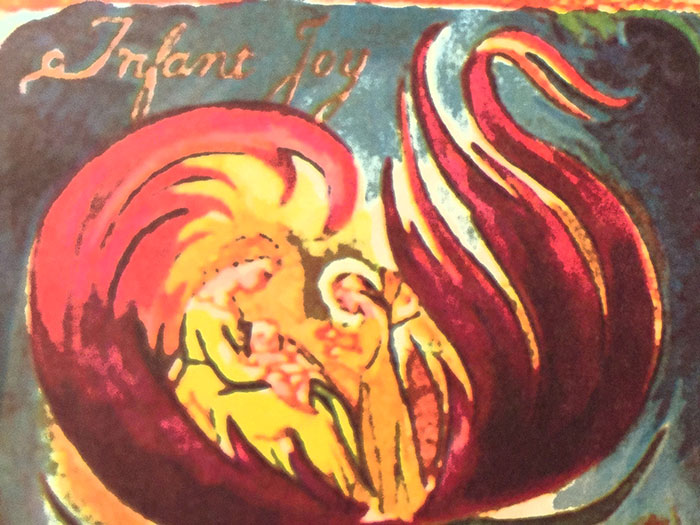

Infant Joy

He asked to be baptized when he was eight. We were thrilled by his decision to publicly profess his belief in the saving grace of Jesus. A few other kids were baptized that same day. They lined up on stairs wearing white robes over their swimsuits, which they changed into in the church bathroom. I sat up straight with a giant grin as tears pooled in my eyes until they fell. Baptisms always make me cry. When it’s your child, it’s doubly beautiful.

It was his turn. He stepped down into the baptismal pool, joining the associate pastor who asked him Do you believe? With a yes, he was rocked back into the water. He was rocked back up. There was no heavenly choir in the room, but somewhere in the invisible they rejoiced. He rubbed his eyes and smiled as we clapped wildly. Later, in the car driving to a celebratory lunch, he noted his underwear was soaking wet. It was annoying him.

“You didn’t take off your underwear when you were baptized? You had your swim trunks!”

He said he wasn’t swimming, he was being baptized. He didn’t know! We laughed. We still talk about his baptismal underwear, which probably had Spongebob or Yoda printed on the fabric. I love the image of my young little man’s baptism being a source of joy and a sign of faith, commencing with the sopping-panted car ride away; soaring and solemn one moment, cold buns the next.

A mother can’t stalk her son’s heart. She can think of advice or anticipate confusions, but she can’t tread inside. She can throw the undies in the wash with a chuckle, but she can’t wash her little boy’s heart clean or empty him of despair.

He’s been new so many times. Someday, a final new will come. With every beat of my heart, I pray it will be in the deep, gauzy future, beyond my little mete of earth.

Laid down on a dark line

My son is still an inpatient at a psychiatric hospital. He is safe, he is taking medication, and he is getting therapy. He will come home soon.

I have a squad of friends and family praying for him and for the rest of our family. I feel it. I’ve been blessed with moments of the most famous peace of all, that which passes understanding. I’ve been blessed with audacious hope, laughter, and being witness to his genuine smile. Visiting hours are short. Each moment feels desperately precious. I want to drown in his words. When I hug him hello and goodbye, I inhale.

The death of my father in June was brutal. I’m still grappling with losing him. But the very real loss of my father is an acorn compared to the oak of the mere thought of losing my son. He was close. For the rest of our lives, we will carry the memories of this grievous time. When the ambulance crew loaded him inside, one of the crew members said they’d take good care of him. Their job was to take him from one hospital to another. My job was to drive home, alone.

The night was cold and I had left my coat in the car when we arrived at the ER 9 hours earlier. I walked from the ambulance bay through a dark parking lot. I was slightly chilled, but the shivers were intense. My entire body, heart, mind, and soul were screaming for the warmth of hope. I remembered my son shivering in the maroon scrubs but denying he was cold. He must have been so afraid.

I was so afraid.

I unlocked my car and sat behind the wheel. When we arrived, I said, “This is going to change everything for the rest of your life. Do you know that?” I wasn’t trying to change his mind. I was being honest and needed to know he understood.

He answered, “Isn’t it better to be here than not?”

With that, we went inside.

I drove to the ER with him. I drove home alone. That’s tough in any circumstance. Packing him into that ambulance with a kiss and my consent was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done and one of the worst moments of my life as a mom.

With the legalities of a 72 hour hold, I felt like I had just signed away my son.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

My son has had three surgeries in his life. I signed consents for all.

I’ve signed him up for schools, clubs, and field trips.

I sent him on a class trip 1,000 miles away. You can’t do that without a signature or twelve.

I’ve sent him to competitions in other states. Again, scritch scratch loopy loop. Done.

Yes, please clean his teeth, I’ve signed.

Yes, please remind him (in an official curriculum-sanctioned manner) how babies are made. I’ll sign that.

Sure, church camp. You may give him Tylenol. Signature required, signature given.

Load up his little thighs and big kid arms with pokes intended to protect him. I understand the risks and demonstrate with my scrawl.

My pens and their pens have propelled him towards scalpels and a western horizon. They’ve secured seats on chartered busses and protection from mumps. They let him zip line over a mountain creek, learn to drive, and tour a gold mine—not simultaneously. With every expressed consent, I believed I was putting him on the trajectory to the beautiful and the worthwhile and the protected.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

That trajectory was a lie. While he had all the right things going for him on the outside, he despaired. We didn’t know at first. He hid it well and went through the motions of being a suburban teenaged boy. One day it became too much to bear and he told. He let it out.

He laid down his name, his words, himself on a long dark line: Help me.

The second worst place in the world

They had my son empty his pockets. He took off his socks and flipped them inside-out so they could see he wasn’t harboring anything under his arches. He was handed a pair of maroon scrubs and told to put them on in the bathroom around a corner. A security guard followed. From my position on a small couch, I could hear crisp knocks. “Are you okay in there?” Yes, he answered. Fifteen seconds later this would repeat. He came out holding his clothes in a wad. A nurse took them and stuffed them into a clear plastic bag. One held a metal detector and waved it over, around, and under him. They told him to join me in a small private waiting area just off the psychiatric intake station.

The maroon scrubs were shiny. I felt a sleeve. He said, “It’s paper, I think.” The top was voluminous, like a pro football jersey without the pads. The bottoms were cropped, hitting him just below the knee, but tighter. He shook, but denied being cold.

The intake station was in constant use. Kids came in a steady stream and were put through the same motions; searched, dressed, stuffed, wanded, take a seat in that room, or that, or that. So many arrived, they spilled into the hallway. The word “epidemic” is not hyperbole. Despair is having a field day.

A nurse named Mike joined us and asked a few questions. Then, he apologized for the setup and decor. “It’s a safe room.” The room contained the small couch, a large chair that appeared to unfold into a bed, and a strange picture of an oddly kind dog. It was covered in thick plastic which was bolted to the wall. Safe, yes. There was nothing in there that could hurt anyone other than the hurt we brought with us. Had either of us had the sudden impulse to try to commit suicide via picture frame, we were thwarted. Kind Dog’s steady gaze was another deterrent.

Mike left. My son was tired, so I moved off the couch to the chair under the dog. He tried to stretch his six feet out into a semblance of comfort, put couldn’t. He continued to shiver and I asked if he wanted a blanket. No.

A woman rolled a computer cart into the room. She introduced herself as a clinician who would gather information to pass along to the psychiatrists. They’d decide what level of care he’d need. I was led out of the safe room and into another larger version down the hall so she could speak to him alone. It was empty but had enough room to seat a dozen. Here, too, the artwork was bolted under plastic.

I sipped water and prayed. I prayed and prayed and prayed he’d be honest and the clinician would be wise. My biggest fear was losing my son, but he was safe so I pivoted my terror to the idea these people would see him as just another crazy kid, literally. There were so many in the maroon uniform. With each of these precious ones were family members. They walked by. Sometimes, I’d catch an eye or they’d catch mine. It wasn’t intrusive or disrespectful. There is great solace in the power of recognition. We weren’t alone. We were gutted and bewildered but shared a common knowledge.

It was better to be bolted under plastic than not.

A children’s psych ward is the second worst place in the world. The first is a funeral home.

Jesus Thinks Your Invisible Potato Salad Needs More Salt

My best friend and I spent an entire day seated on a blanket spread in my living room, announcing we invented a fun new game called “invisible picnic”.

It was boring. Invisible fried chicken legs were tasty for .3 seconds.

It was stressful. Every time my mother was near, we felt the need to ramp up our pathetic pretending. “Mmmm, pass the watermelon!” we shrieked through tight smiles.

It was futile. Eventually, my friend had to go home and the blanket had to be pulled off the yellow carpet.

Earlier, we were being silly and careless when we knocked a large potted plant off a table. It hit the floor and dumped freshly watered dirt in a messy mound. We frantically scooped most of it back into the pot. I felt nauseated when I realized the dark, wet dirt left a large stain. I raked at it with my fingers. I ran to get a wet towel and tried blotting, but I’m sure I only made it worse by re-wetting the drying dirt and pressing it down further into the fibers.

My mom couldn’t see it! She would probably make my friend go home. She’d yell with her bottom jaw jutted forward. I hated that. Why ruin a good day with honesty and contrition? The stain needed to be hidden. Using a blanket was an obvious choice, but how to explain? That’s where one of us brilliantly thought “invisible picnic” and the other agreed.

That day was completely burned away by our ruse. Nobody has ever been so dedicated to faux outdoor dining as we were. As afternoon grew into evening, the light in the living room darkened. She had to go home, four doors up the street to a mom with unspoiled carpet. Luckily, the diminishing light helped to mask the blotch and the rest of that day proceeded with no drama. It was over. We succeeded in fooling my mom.

It took days for her to notice because she usually cruised by the living room. Her path commonly took her from bedrooms to kitchen and back again. The living room was a place nobody actually lived. We did that in the family room, where the TV was enthroned. When I heard her yell, “What happened here!?” there was enough distance I could plausibly shrug my shoulders and express deep concern. I had two younger siblings. It was probably one of them.

I persist on unfurling blankets over my sin or, lately, my sorrow. Unlike my mom, Jesus isn’t thrown off by well-placed blankets and invisible potato salad. For added cover, I sit on the blankets and pretend I’m having a wonderful time. This chicken is perfectly fried. This watermelon is the sweetest seedless I’ve ever devoured. This lemonade is cool and tart. My belly, which should burst with such a spread, remains predictably empty.

As I’ve grown, these ruses are less common as I’ve been seated at real feasts by Jesus himself. There’s no competition between what I conjure on my own and the reality of his forgiveness and my redemption. He tells me to get off the floor. He peels back the blanket. We consider what’s underneath and he cleans whatever we find.

When yellow and blue make nothing at all

From The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows:

Exulansis

n. the tendency to give up trying to talk about an experience because people are unable to relate to it—whether through envy or pity or simple foreignness—which allows it to drift away from the rest of your life story, until the memory itself feels out of place, almost mythical, wandering restlessly in the fog, no longer even looking for a place to land.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

My father looked through me as he died. His coffee-brown eyes blazed with an amber-like illumination. They glowed. His black pupils were the size of peppercorns and appeared to be suspended in the petrified grasp of ancient sap. My sister and I turned to the nurse and insisted, strongly, those were not our dad’s normal, everyday eyes. It was desperately important—to me—she understood the forces at work in that room at that moment. “They’re beautiful,” she said. As a hospice nurse, she saw death daily. Looking back, I know she was aware my dad would be gone within minutes.

I had never witnessed anyone die. Dutifully, I had read all the hospice brochures outlining patient care. The most solemn pages listed common signs of imminent death but there was nothing about eyes that appeared to be focused on something invisibly bright.

His eyes were locked on something I couldn’t see but could feel. His time has come, child. I asked everyone in the room to give me 30 seconds with him, alone. I rattled off an audacious, but short, to-do list and pleaded with him to run to Jesus. Run. Then, I frantically called the rest of my family back into the room to be by his side. He was still breathing. With every exhale his lower jaw jutted forward in a snapping motion, as if he were trying to eat the air. We pressed our hands onto his body and cried words of love. His jaw stopped reaching. His chest stopped rising. His eyes stopped glowing.

Without a stethoscope or medical training, each one of us leaned away from his body and looked at each other in agreement. He was gone. I can’t say what anyone else was feeling or thinking. I was stupefied, bewildered, and grateful to have been given such a gift; to watch a beloved one gaze at glory’s indescribable light.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

When I came upon the word exulansis a few days after my dad died, I recognized its truth. It was coined by a man named John Koenig for his innovative tumblr, The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows. He wrote of the word’s origins at Facebook: “From Latin exulans, “wanderer,” after the Latin name of the Wandering Albatross, diomedea exulans. Albatrosses spend most of their life in flight, rarely landing, going hours without even flapping their wings. Like they’ve disowned the earth, but can never leave it. And of course the albatross is a symbol of good luck, a curse, and a burden, and frequently all three at once. Sounds about right.”

Sounds about right.

I’ve only told a few people about my dad’s eyes. When I do, I immediately regret it. Eyebrows rocket up. The person blinks, then nods. “Wow!” Head-tilt to the side.

I guess you had to be there.

Each time I tell someone, it diminishes. Doubt flares.

Maybe it was exhaustion, grief, a desire for meaning, his medications? I speculate I got it all wrong that day in that room. The Light of the World was there; or maybe it was the way the sun bounced off a car across the street, then off the wall he was facing? I still believe my dad was saved. But that outlandish sense I was witness to something miraculously beautiful in room 238 is threatened…by me.

Was this what it meant when Mary “kept all these things and pondered them in her heart”? (Luke 2:19) She knew others would find her experiences not only foreign, but beyond rational explanation. The shepherds told of a host of angels singing over a newborn king. She did not. As she rocked and nursed her little one in the coming days, weeks, and months, she must have revisited that holy night. She sank into the sweet hay of memory, finding a fogless place to land.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

There is no way to share everything that transpired between my dad’s diagnosis, his death, and his memorial service. It’s not necessary, nor do I want to broadcast everything that happened. It’s also impossible to adequately capture the magnitude of continual mercies. Each arrived like an arrow, swift and true: A burst of energy here, insight there, peace, the perfect song, a bite to eat, roses blazing fragrance, the moon and stars aligned in the west, a hand squeeze, an inside joke, clean sheets, a well-timed visit, outrageous challenges.

The one-month mark looms later this week. I’m learning what grief is and what it isn’t.

Grief is a state of mind that continually flings itself to the past to rehash what happened.

Grief is a state of mind when the present is invaded by unexpected reminders of the person lost.

Grief is a state of mind when you accept the future as a dad-less place, empty of the color he brought.

It’s like a rainbow with the green sucked away. It’s not right. It’s not normal. How can yellow meld into blue without wheezing green? It’s impossible to picture an abrupt line in a rainbow outside of bumper stickers and Lisa Frank notebooks. Grief is the most impossible emotion to grasp, and that quality of grief is what makes grief, well, grief. It is confusion tinged with wary anticipation. It’s nonsense, like a green-less rainbow or a dad-less me.

In A Grief Observed, C.S. Lewis grappled with the same desire to define grief. In chapter 2, he wrote:

“And grief still feels like fear. Perhaps, more strictly, like suspense. Or like waiting; just hanging about waiting for something to happen. It gives life a permanently provisional feeling. It doesn’t seem worth starting anything. I can’t settle down. I yawn, I fidget, I smoke too much. Up till this I always had too little time. Now there is nothing but time. Almost pure time, empty successiveness.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I think Lewis would have appreciated the word exulansis and the definition even more. It’s helped me pin down new emotions and enabled me to not expect others to fully get it. Of course they don’t, just as I don’t understand how my widowed mother gets through the night. Or the morning. Or the afternoon. I have the strong impression, however, she must have been gifted with her own “illuminated eyes” moment along the way. It’s something she ponders. It’s something she treasures. It’s something she may have tried to express once or twice but found diminished and returned to her with a stain.

You can grieve alongside someone, but you can’t share it like a sweater or split it like a cookie. Telling our stories of what happened is an attempt to split it away—at first. If I say it enough, maybe I will believe it.

My dad died.